In an earlier post, I outlined some fundamental aspects of design thinking and how it supported the new venture realization process. For the following three parts, I want to look at the famous (and possibly infamous) IDEO Shopping Cart design video to answer one question – Are the lessons derived from this archival document still relevant?

In part one, I will look at diversity and how the video depicts it, and some ways to view this representation. In the following sections, I will look at the efficacy of their “deep dive” techniques, followed by IDEO’s take on innovative culture.

Part One: On Diversity

Introduction

As an introduction, I have been showing this video in classes on and off since its initial production in 1999. The IDEO shopping cart video premiered as an episode of ABC Nightline in 1999. To demonstrate their unique innovation process, they decided to design a grocery store shopping cart that addresses specific issues experienced by grocery store owners and shoppers. The show concentrated on two major themes, the design process, and the IDEO culture, enabling sustained innovation. The video followed a multi-disciplinary design team as they moved from initial on-the-ground observation in grocery stores and secondary market research to their unique form of brainstorming, prototyping efforts, and soliciting customer feedback. Following the team for five days, the narrative weaves in and out from the design process activities to a tour of IDEO’s environment and cultural artifacts.

As an educator who studies innovation’s cognitive and behavioral dynamics, the video’s two themes present valuable lessons to discuss further and explore. I have facilitated dozens of classroom discussions about the details of the design process and the organizational practices that enable innovative behaviors and outcomes.

Today there are many definitions of design thinking. But, like every significant construct, there is plenty of disagreement about how to best place it within the scope of creative and innovative thought processes. A good starting definition covering much ground is “a human-centered innovation process that emphasizes observation, collaboration, fast learning, visualization of ideas, rapid concept prototyping, and concurrent business analysis” (Lockwood, 2009).

Design thinking is a systematic approach to solving significant problems. It begins with a “human-centered” discovery process, followed by experimental and iterative cycles of solution design, testing, and refinement. From a cognitive science perspective, the structured nature of design thinking allows problem solvers to investigate an effective solution without being thwarted by their own biases and behaviors that impede innovation. In addition, design thinking emphasizes deep empathetic customer engagement to facilitate the co-creation of optional solutions.

Now, let me take you to the start of the video and how it introduces and sets up the video’s premise.

Lesson One – This is not your 2022 diversity

In the 15 minute version (the one I use in class), the video starts – “9 in the morning day one and these people have a deadline to meet.” After briefly highlighting some of their successful and failed product designs circa the late 1990s, Dave Kelley positions IDEO’s design approach. “We are not actually experts at any given area. We are kinda experts in the process on how you design stuff. “

From this initial preamble, we meet the team assigned to bring the design of the shopping cart into the 21st century. The group described as “eclectic” are individuals who derive their ideas from a diverse range of sources. The narrator introduces the core team with disparate backgrounds in engineering, psychology, architecture, marketing, linguistics, and biology. Therefore, the message focuses on disciplinary background and domain expertise only. In the 20 seconds of the video, the narrative does not mention gender, ethnicity, or other forms of diversity. And one of the first learning opportunities presents itself. Circa 2020 and onwards, student discussions focus on the apparent lack of diversity in the video. I have found it essential to bring up this deficit before showing the video. One particular program has requested that we not show the video. This 20 seconds of video has led to hours of class discussion.

So let’s double click on this. As a starting point, I want to reflect on my experience with organization innovation in the mid to late 1990s. Briefly, I was conducting a study on the cognitive-behavioral drivers of organizational innovation. As part of the study, a behavioral model was designed and tested, based on comparing behaviors and organizational practices of firms with high versus lower rates of innovation. I identified several behavioral characteristics across four categories – advocative, collaborative, inquisitive, and goal-directed. One of the behaviors that stood out as strongly correlated with innovation outcomes as part of the inquisitive category – “search for and incorporate diverse points of view.”

The research studies associated with this work led to several applications in most prominent technology companies, like AT&T Bell Labs, Becton Dickinson, and General Instrument. We found several organizational practices that fostered employee inquisitiveness during interviews with company leaders, scientists and engineers, and product development teams. Across the board, we found these highly innovative companies had established programs that promote continuous information from multiple sources, both internal & external to the organization. Standard programs included technical forums & speaker programs, extensive linkages to universities, and formal monitoring of outside technological advances.

Then there was “diversity” training. Almost every organization visited in the late 1990s had diversity training. The focus is on gender diversity only and the human resource departments as the facilitator. The explicit goal of the training activities is to develop the skills necessary to treat everyone with equal respect. The implicit objective was to reduce instances of sexual harassment in the workplace leading to expensive lawsuits and negative publicity. The content made this clear, a discussion of legal regulations and company policies, along with a case study highlighting a spectrum of behaviors with associated consequences. The message was clear; bad behavior is not acceptable in this company. So follow the guidelines or else.

If you look at the history of diversity training at this time, very few programs focused on inclusivity and equity as a moral imperative. With notable exceptions like IBM and Xerox (Anand and Winters, 2008), the focus continued to be on compliance first, and then maybe an inclusive culture. Anand and Winters report that you begin to see a shift away from compliance and more towards respecting people’s differences in the later 1990s. At this time, most organizations deemed diversity training tangential to core business objectives. This circumstance tracked with what I was seeing during this period.

None of these companies communicated any relationship between embracing diversity and organizational innovation and performance in our research discussions. There were no conversations about how diverse perspectives can lead to disruptive ideas. In our meetings with participants, no one seemed to take this training seriously and found it a waste of time. At the time, I felt this was a missed opportunity. These organizations gathered some of the brightest and most creative people globally and provided them with a list of dos and don’ts. Leadership could easily have framed the training differently, demonstrating how embracing a diverse and inclusive workplace would positively impact both individuals and the organization.

One can surmise that IDEO was grappling with these issues like many firms at the time. The core team has six members in the video, four men and two women. [Note: A patent for the design filed on 12/10/1999 included Peter Skillman, the IDEO engineer, the lead author, and five other men.]

IDEO seemed to nod to gender as part of their “eclectic” mix for the video, with no explicit representation of ethnicity, race, or age. But, again, this may reflect a sign of the times, reflecting what David Thomas and Robin Ely call the “discrimination – and – fairness paradigm.” Their HBR article (1996) defines this paradigm as looking at diversity through the lens of equal opportunity, fair treatment, and compliance. In other words, making sure that the composition of the workforce reflects more closely that of society. While this is not an excuse, it reflects the common thinking among many companies during this period.

Additionally, there was a good deal of discussion about the representation of women in the technical fields. In reports by the National Science Foundation, women represented only 28% of employed scientists and engineers in 2010, up from 23% in 1993. The discrepancy between genders in the STEM fields continued as part of an ongoing discussion in the U.S. in 1999. I was associate dean of undergraduate students for Columbia Engineering at the time. We were very focused on increasing the number of women enrolled in our engineering and applied sciences programs, which was around 25%. In the U.S., the women engineers were hovering around 13%, up from 9% in 1993. Today, women hold only 15% of engineering jobs, still one of the most underrepresented STEM fields.

The data is quite discouraging if you add women of color into the picture. As of 2020, women of color hold 12% of the tech positions in the U.S. Women who identify as Asian or Pacific Islander hold 7%, Black or African American hold 3%. Women who identify as Latina or Hispanic have 2% of all tech positions in the U.S. Women who identify as white hold 13% of all tech jobs in the U.S.

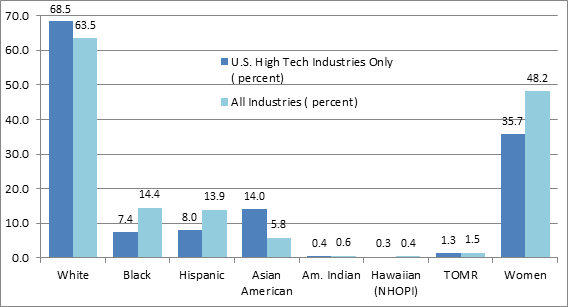

IDEO was very much part of the Silicon Valley environment. If you zoom on Silicon Valley, gender and ethnicity representation was woeful. In a 2014 U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission special report, investigators looked at the participation rates by gender and race, comparing the tech industry with all U.S. industries, emphasizing Silicon Valley. Overall participation rates of whites, Asian Americans, and males in U.S. high tech industries were disproportionally higher, especially in the Silicon Valley geographic area. African Americans and Hispanics were under-represented nationwide in the high-tech sector compared with the private sector. African Americans and Hispanics were significantly under-represented in the high-tech industry in the Silicon Valley geographic area. Additionally, women lagged behind men in leadership positions and technology jobs, as Technicians and Professionals, in the high tech sector. These gender differences were predominantly evident in the high-tech industry of Santa Clara County.

Lessons from Research & Application

Now, here we are in 2022. A growing wave of research and practice indicates a relationship between diversity and organizational performance.

McKinsey has been writing a series of research reports about diversity, dating back to 2015. Their latest 2020 series report engaged 1000 large companies across 15 countries. The information pulls no punches as it finds slow progress in building diverse representation in participating firms. However, a positive trend demonstrates that lasting cultural change is possible with a systemic, business-led focus on inclusion. Due to the longitudinal nature of the McKinsey research, they can correlate progress in expanding gender and ethnic diversity in senior leadership and key performance indicators. Companies that have made the most progress – fast movers” in developing representation and radically creating an inclusive culture have outperformed the “laggards” substantially in terms of profitability growth against national industry averages.

In today’s top organizations, leadership agrees that diversity drives innovation. For example, in a recent Forbes Insights Report (2011), survey responses of 331 senior leadership strongly agreed that a diverse set of experiences, perspectives, and backgrounds is crucial to innovation. Moreover, these leaders see the value of encouraging different perspectives and ideas that lead to new products and business innovation. But, of course, the one problem in a study like this is that we don’t know how leadership was defining or measuring innovation in their respective industries.

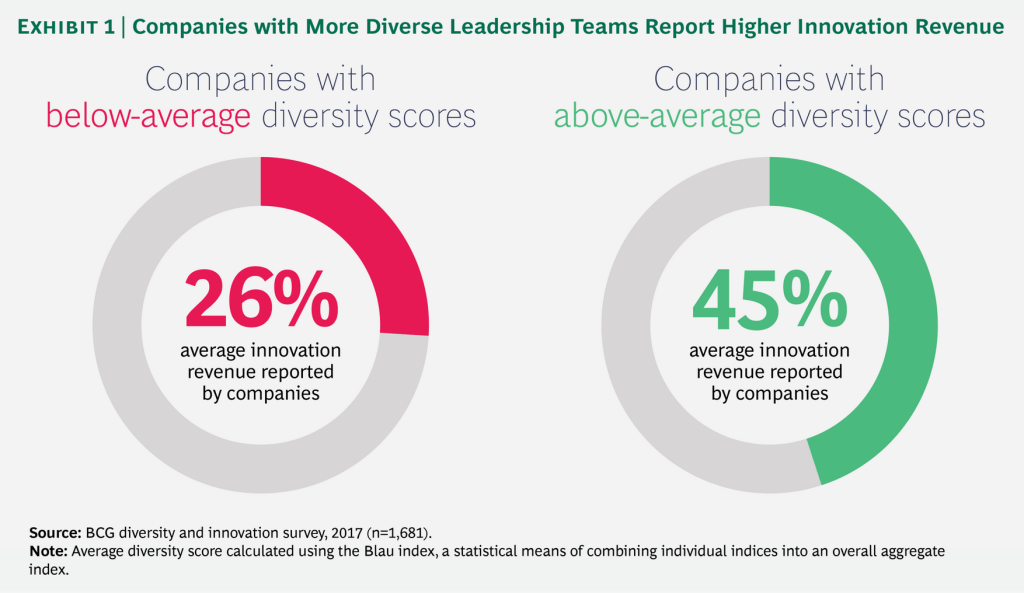

As has been the case for many years, it is challenging to find studies directly measuring innovation performance. One of the best innovation performance measures identified in my earlier studies was the revenue or profitability generated from new products over three years. 3M was the first company to popularize this innovation metric. Many firms have since adopted it over the past couple of decades. A 2018 BCG report investigated the relationship between diverse leadership teams and this innovation metric. BCG found a strong and statistically significant correlation between the diversity of management teams and overall innovation revenue. Companies that reported above-average diversity on their management teams also reported innovation revenue that was 19 percentage points higher than that of companies with below-average leadership diversity—45% of total revenue versus just 26%.

In a recent study investigating the relationships among diversity, inclusive practices, specific organizational characteristics, and innovation, the researchers examined several aspects of various industries across the UAE. The authors developed a model to investigate the direct and indirect relationships of three exogenous constructs: workforce diversity, inclusion practices, and organizational characteristics with one endogenous construct of organizational innovation.

I liked several aspects of this study. First, they collected both inherent and acquired diversity characteristics. This study’s inherent level of diversity includes age, gender, ethnicity, disability, and native language. Secondary level diversity information had marital status, parental status, religious beliefs, and work background.

The second construct, inclusion practices, collected information on work arrangements that facilitate the inclusion of diverse employees in the organization without any discrimination. The inclusion practices investigated included fairness, belongingness, uniqueness, and a diversity climate. The authors define fairness as the employees’ perception of the organization’s fairness in management policies, interpersonal treatment, and equitable distribution of opportunities. Belongingness manifests as acceptance by the group and the sense of connection with its members. Next, the study defines uniqueness as an individual’s perception of a differentiated understanding of self. Finally, diversity climate is the inclusion of people from diverse backgrounds and how their contributions are valued.

The third central construct was labeled organizational characteristics. Here the researchers limited (and I think rightfully so) industry classification, corporate type (public, private, not-for-profit), and firm size by the number of employees.

The study investigates how the three constructs influence organizational innovativeness. Respondents rated how their respective firms implemented new or significantly improved products, processes, or business practices in a survey.

Over two weeks, 511 surveys across 13 different industry classifications. The investigators found a significant and robust correlation between inherent diversity and organizational innovativeness. There was no meaningful relationship between the second level of diversity (acquired) and innovativeness. The direct impact of inclusion practices on organizational innovativeness is significant across all variables. Fairness and belongingness have the greatest influence. Organizational characteristics played an insignificant role in this study.

While the study has its limitations, especially a sample all from the same region, it demonstrates the role that primary or inherent diversity, along with the integration of inclusive practices, has on an organization’s capacity to innovate and adapt to a changing marketplace.

As industries grapple with how to improve representation, create more inclusive cultures, and capitalize on its impact on performance, the sciences have been investigating the relationship between diversity and such outcomes as creativity and innovation.

In “How Diversity Makes Us Smarter” (updated from Scientific American), the late Columbia Business School Professor Katherine Philips makes it clear how “diversity jolts us into cognitive action in ways that homogeneity simply does not.” There is little doubt from cognitive studies that diverse perspectives broaden viewpoints on issues and can readily lead to new ways of solving problems. Similar to what I noted in my earlier innovation studies, soliciting multiple views leads to novel, flexible thinking, a key to innovation.

Professor Phillips noted several studies demonstrating how such factors as gender and ethnicity created what she calls informational diversity. She argues, “when people are brought together to solve problems in groups, they bring different information, opinions, and perspectives.” In one study, Dezso & Ross (2012) found a relationship between the size and gender of leadership and its impact on financial performance, including a metric, “innovation intensity,” measured as a ratio of R&D expenses to assets. This study found that companies with more significant numbers of women in senior positions prioritized innovation, leading to more substantial financial gains.

Conclusions

When you consider how we view diversity today, the IDEO video does not directly serve our needs as educators or students of innovation. However, as an educator, I think that one can use the video’s portrayal to facilitate a robust discussion with the suitable preamble.

My students clearly state that embracing diversity is the right thing, period. However, whenever someone brings up the importance of associating diversity with performance outcomes, many find this conversation frustrating and wrongheaded (and this is business school). Well, I am much older now since my earlier innovation studies. Still, my views have not changed in that organizations should embrace diversity, equity, and inclusion as both a moral imperative and a good business strategy. If you don’t embrace diversity with this attitude, you won’t achieve an innovative culture and performance outcomes.

Part 2: On the Deep Dive

In our last post, I started a series exploring the validity and applicability of IDEO’s shopping cart design video in 2022. I have been showing this video on and off since its initial production in 1999. Unfortunately, some of the content has not aged well, particularly its depiction of diversity. The last post offered a considered overview of this inadequacy.

The focus will be on the IDEO design process itself for this post. This review aims to break down the design process into each major component and review it as presented in the video.

Early in the video, Dave Kelly, one of the founders of IDEO, explains to the ABC Nightline reporter that “we are not experts at any given area… we’re kinda of experts on the process on how you design stuff”. He explains that they can apply their process in the service of innovating in any product or service area. The demonstration of the IDEO process is at the heart of the video. The video weaves back and forth from their design process as applied to the shopping cart to a guided tour of IDEO’s unique work culture (the subject of the next post).

When I think about the design thinking process, I consider framing the problem, gathering customer discovery & market data, designing & testing potential solutions, and finally, soft launching to determine how the solution works in the natural customer environment. The approach focuses on a deep understanding of a problem that our customer or stakeholder is trying to solve. The best solutions come from a deep understanding of what the customer is trying to accomplish and the frustrations experienced along the way. By diving into their everyday experience and challenges, you will begin to see ways to add value to their current situation. Sometimes, you will see the issues even when they don’t.

The storyline takes through what may be considered three significant phases of design thinking, exploratory, idea generation, and prototyping & testing. The project team gathers information about the problem and the user or customer’s needs in the exploratory phase. During this phase, teams apply several techniques, including direct participant observation, journey mapping, and user interviews. The idea generation phase allows the team to transition from divergent thinking, generating multiple ideas, to convergent thinking, where initial ideas develop into feasible solutions. Several tools support the ideation phase, including brainstorming techniques, mind mapping, and cluster analysis. The final phase focuses on designing and building early solution prototypes to solicit feedback from all relevant stakeholders.

Exploratory Phase

The video begins the process with the core team of designers reviewing information and data that they have gleaned from what I suspect are some early secondary research sources. I surmise that they are conducting a preliminary screen of the current state of shopping cart design and use before they start what design thinking experts call the “observation” stage.

Acknowledging that these video productions are edited and condensed for clarity, the early group discussion is not in context. But I agree that there needs to be preliminary research to design a protocol that leads to unbiased observations of shopping cart users and other associate stakeholders. So what do they find out? From the video, one surmises that the team set out to review the information currently available on shopping cart design and known problem areas.

The first area they focus on is one child safety, with a team member reporting on injury and hospitalization data occurring in supermarkets associated with shopping carts, to the astonishment of the group, the data reported over 22,000 hospitalized injuries per year. What prompted the exploration of safety is not known, but the design team quickly stumbles upon a significant problem area. A problem in which we, as a society, have made little progress.

Another issue that comes to the surface during this early research phase is the theft of shopping carts. According to the Food Marketing Institute in Washington D.C., annual costs due to cart theft are around $800 million.

At some point, the team leader suggests that they create a list of any questions they want to ask during grocery store site visits. So the preliminary research helps to shape the observational and interview strategies for the planned visit. The team is then divided into groups by specific problem or need areas and sent to the site to meet with people who “use, make, and repair “shopping carts. “The trick is to find these real experts so you learn much more quickly than you could then by doing it the normal way, trying to do it by yourself.” Dave Kelly notes that the process at this stage is like a social scientist that is studying tribal culture and observing behavior to understand the problem or need best.

After a 2-hour site visit, the teams returned and shared everything they observed and experienced. Then, as becomes apparent, they identify four major user need areas, child safety, cart theft, shopping process, and locating specific food items.

One of the questions that occurs while watching the video is who is the actual customer? Of course, this challenge is part of a news piece and one where the objectives are not market-driven in the typical sense that there is a problem to be solved for an actual paying customer. This lack of customer focus leads to a lack of clarity regarding the problem definition and pain points experienced by the stakeholders involved. One of the discussions we have in class starts with the question, who is the customer for this shopping cart? About a third of the way through the video, Dave Kelley emphatically states that the team has to make sure to integrate the needs of the store manager. Is the store manager the ultimate B2B customer? Unfortunately, the video does not indicate what discussions, if any, took place with store management. In a market-driven scenario, management is part of the initial discussions and, most likely, specific product attributes outlined. For example, management may have stipulated that any new shopping cart must cost around the same as the current price. While a reasonable request, it would have placed specific constraints on the design solution.

One can’t retrospectively know how the needs-finding process would have been different if management had been more involved in the early engagement. You can say that you would have still wanted to observe and interview the direct users of the shopping cart, much like IDEO’s team. You would want to talk to parents about their concerns regarding child safety, observe regular customers shop and compete them with professional shoppers, and speak with others directly or indirectly involved with maintenance and care of the carts. There is no doubt that the concerns of store management and shoppers combined would have created a different set of needs and concerns. It would be up to the design team to tease these out and make a design that would optimize the solution for all involved parties.

I frequently ponder the sequencing of these exploratory design steps on the process itself. If you consider the first two stages in a traditional design thinking process – observe and understand, one wonders about the optimal order of these two tasks. Do you first observe cold with minimal research that might lead to biased observation? Or is there a suitable amount of preparation that helps you optimize your observations? For example, in the video, the team was quite astonished to learn of the data on child injury. What did they do with this knowledge once they started to speak with parents during the site visit? How did they formulate their questions to the parents? Did they lead parents to talk about their concerns regarding child safety? Would it have come up as a topic if it had not been explicitly referenced? On the other hand, knowing this issue may facilitate a state of awareness that increases your observations of parent and child behavior while shopping.

In the end, I tend to lean towards the benefits of preparation to make sure that you use your observation and discovery time optimally.

Another benefit of preparation is how it may influence the design team’s ability to empathize with the user’s situation. One of the core skills required for successful problem solving is the capacity for empathy. Design thinking processes are structured to develop and enhance your understanding of the customer and their experience. From the start of the design process, you are laser-focused on understanding the customers’ experience with what they are trying to accomplish and the obstacles. Like an anthropologist, you investigate the customer experience and learn what they are doing and what is going on with them emotionally. As part of this investigation, you are also hoping to learn how they currently work through the problem or task in question, including any solutions to eliminate or minimize obstacles. By probing these current solutions, you begin to gain insight into how they would like to see things work functionally and emotionally. This empathetic work leads to insight into what would make their life better in this situation.

While the research on empathy can be pretty confusing, I believe that it shows that certain types of preparation can lead to a more empathetic outcome. For example, research shows that priming a person to empathize with a specific pain point or challenge intentionally will increase the substantial degree of empathy when presented with the target person. In addition, it is common practice to build empathy through storytelling in the design thinking world. For the above reasons, I have founders create customer journey maps before their discovery interviews. The act of narrative building primes the person to listen to specific aspects of the customer’s experience. If the particular elements of the experience do not come up during an open interview, you can probe later (keeping in mind that you initiated the thought, not the customer). Look for any corresponding research on empathy and primings, etc.)

Idea Generation Phase

Once the IDEO team returns from their site visit, they start by sharing everything they have learned during the visit. This initial sharing begins the “deep dive.”, a total immersion into the problem. As you will see, the deep dive is a variation of what may be considered the traditional brainstorming process. But as Tom Kelley notes in his book, The Art of Innovation, IDEO works very hard to optimize the brainstorming process, considers it a practice, and continually experiments with ways to improve its application.

While many people give credit to Dave Kelley and his colleagues at IDEO for formalizing human-centered design or design thinking, they certainly did not invent brainstorming. The concept has been around since 1938, when Alex Osborn, an advertising executive, introduced the term and popularized it through his writings. In 1953 he published “Applied Imagination – Principles and Procedures of Creative Thinking,” He outlines the steps that are now quite familiar to anyone who works in groups and solves problems.

Osborn listed four main guidelines that will sound similar to those applied by the IDEO team. The rules outlined in his book include:

- No criticism of ideas.

- Going for large quantities of ideas.

- Building on each other’s ideas.

- Encouraging wild and exaggerated statements.

Compare these tenets with IDEO’s guidelines as presented on large signs in their meeting rooms.

IDEO Deep Dive Guidelines:

- One conversation at a time

- Stay focused on the topic

- Encourage wild ideas

- Defer judgment

- Build on the ideas of others

As a technique to generate ideas to support the solution of a problem, group brainstorming has been around for quite a long time. But does it work? The research is far from clear. In a significant review of the brainstorming research, Paulus and Vincent R. Brown (Hofstra University) found that group brainstorming is not the most effective way to generate new ideas. They argue that the group process does not yield as many ideas as individual brainstorming. At times, members have to delay speaking and may lose track of their thoughts, getting distracted during the sharing process. They suggest that one way to avoid this issue is to have people write down their ideas and share them in written form, “brainwriting.” Their paper tests a few different mixing methods of sharing – writing and vocalizing. Although a small sample size, the act of writing ideas seemed to impact the number of ideas positively.

As seen in the IDEO video, facilitation helps. Research has found that the effectiveness of brainstorming in interactive groups can be significantly enhanced by having a trained facilitator. The facilitator helps to enforce various rules that support the number of ideas generated. These rules help keep people talking, stay focused, and encourage everyone to contribute. Without the proper facilitation, brainstorming efforts will be less effective. Beyond this post, much research highlights barriers to effective brainstorming outcomes, including individual apprehension to sharing ideas in groups, low productivity due to competition for speaking time, and lack of anonymity.

Beyond facilitation, other cognitive factors impact the efficacy of brainstorming. For example, individual participants’ capacity to attend and retain the ideas of others help to stimulate new associations – building on the opinions of others. One of the best practices that IDEO has developed for preparing participants for a brainstorming session is having members participate in some warmup activity. As Tom Kelley notes, sometimes it helps the team to focus during the deep dive if they participated in an earlier warmup activity. The warmup aims to stimulate a mindset to transition attention to the problem. Activities like a “show and tell” trip help establish the right frame of mind to focus attention and awareness on the brainstorming activity. For the shopping cart challenge, the site visit to the grocery store serves this purpose by creating a standard frame of reference and focus supporting the ideation session. As a facilitator of the brainstorming session, bringing the participants back to the site visit can create search cues that bring back potentially helpful images and thoughts from long-term memory in support of the ideation process.

Earlier in my career, when I was teaching engineering design, I would frequently kick start a project by taking the class on a site visit. One summer, my class was tasked to assess and provide design solutions to support ADA compliance across New York City’s Zoo system. Like the IDEO process, after conducting some preliminary research into ADA compliance and assistive technologies, the Zoo visits served as both inspiration and a framing mechanism. Upon return from the visits, students were able to share what they observed, and the class was able to see needed areas to be addressed. In this case, the need areas ranged from ride accessibility to exhibit signage. These visits enhanced the subsequent brainstorming sessions and eventual design recommendations.

The cognitive diversity of the group increases the range of ideas generated during brainstorming sessions. As the IDEO video illustrates, having participants with various experiences and knowledge facilitates creative ideation. That said, as we discussed in the last post , the diversity of the participants should go beyond cognitive experiences. As a thought experiment, think about the outcomes of the IDEO deep-dive if the participants represented a broader demographic?

After watching the IDEO video, a recent student shared a story about how local grocery stores in the area tackled the problem of the removal of shopping carts from their property. Shopping carts showed up at large multi-residential seniors’ high-rise buildings in the local area. Seniors would transport their groceries and shopping supplies to and from various grocery stores and discard them at the buildings’ front entrance or parking lot. This situation was causing a problem both for the grocery stores and the city housing authorities.

Understanding the cause of the missing shopping carts and the reasons for the behavior, the city, grocery merchants, and tenants could find solutions to reduce the behavior. One of the solutions included the provision of free transportation from the shopping locations to the residential areas. Providing alternative transportation reduced the need for shopping carts by the residents. You can imagine that if IDEO had a more representative membership with knowledge and experience of the local community dynamics, the design specifications around theft might have gone a different way. After all, the IDEO design would not have necessarily stopped the above behavior – residents would have hung the shopping bags on the provided hooks and taken the carts off-premise with their groceries in tow.

Much of the most recent research has looked at electronic brainstorming techniques, distributed virtual sessions, and metaverse sessions. In trying to avoid some of the earlier problems associated with verbal brainstorming, many researchers have turned to electronic methods to stimulate and collect ideas. Allowing participants to enter their ideas into a program and monitor the ideas of others simultaneously results in a higher quantity of ideas. Of course, this method is not without its challenges. There is no guarantee that participants can attend to what is being shared by others while thinking about their idea. That said, the literal capturing of the ideas for review later is a compelling outcome.

Most brainstorming programs support the collection, monitoring, prioritization, voting, and elaboration of ideas generated. There is no magic bullet here, and facilitation and training are still required to optimize these tools. These brainstorming tools are beneficial as you move from divergent to convergent thinking. Starting with the ability to visualize the ideas and move them into clusters, making connections using mind mapping techniques helps focus on the interconnections required to transition from concept to application. Research shows that focusing on subsets of ideas usually results in a more significant number of ideas within the category and increases the novelty.

Again, if you think about the IDEO non-electronic version, they moved from ideation to categorizing, prioritizing by voting, and then transitioned to solution design and prototyping. As with many of today’s software solutions, the IDEO process uses visualization extensively. You can see that small groups of people are sitting together, making sketches, sharing them verbally, and then pinning them to the walls around the room. While it is not clear from the video how the ideas and drawings are categorized, I surmise it is by the need area.

Once generated, ideas are displayed on the walls around the room. From here, the team narrows down the ideas by voting. Design team members walked around the room voting via colored-coded post-it notes. An essential element of the voting process is meeting specific product design criteria. For example, the team leader reminds everyone not to vote for an idea that cannot be built within the challenge’s time frame. After idea generation, teams evaluate the shared ideas and prioritize ideas for further development. You may assess ideas on several dimensions: novelty, feasibility, utility, and impact.

One of my colleagues asked the class during a recent video showing, does voting work? Well, the research seems limited on that subject. However, one can surmise from the decision-making research that you train team members to evaluate ideas against the criteria; a certain amount of calibration occurs, making the voting more valid. Without training, the judgment behind the poll can be inconsistent and lack validity. A clear understanding of the voting criteria will help alleviate the common biases found during divergent thinking, favoring feasible over novel ideas.

Finally, does diversity support convergent thinking? From a research perspective, there is little work on multiple perspectives’ impact on building on ideas, prioritizing, and early development. Intuitively, it should help as it does with generating ideas. But, again, training may be an essential element in this phase. As noted in the diversity research on innovation, one possible barrier can be the challenge of reaching a consensus when the team members represent a wide range of perspectives.

While the video does not convey all the nuances of the process, it is clear that IDEO takes the approach seriously and treats it as a practice, one where everyone gets better over time.

Prototyping and Feedback Phase

The team begins to build physical prototypes from the deep dive ideation and prioritization sessions. I believe how they structure this prototyping phase is the most compelling for students and founders to observe.

Its starts with a transition point, where a “self-appointed” leadership team discusses the best way to proceed and refocus the various groups’ efforts. Something that I will come back to in a later post, but this brief period of “autocratic” decision making is an essential structural procedure that helps innovation happen. In this case, the IDEO design participants are restructured into four need areas to build mockups – shopping, safety, checkout, and item location. At this point of the process, it is common to refocus the targeted need areas.

The most important lesson from the video, in my perspective, is IDEO’s decision to split the design teams into the four need areas, each team focusing their design efforts on a potential solution to the specific problem area. For example, one design team worked on designing the child seat to improve its safety. The prioritization of the four need areas and then further limiting the scope of each design effort is an excellent example of minimal viable product development. In the IDEO case, they work on four need areas separately but concurrently. For many startups, this would be too broad of an effort. But with the right capabilities and, in this case, an extreme time constraint, the process makes sense.

It mimics the classic MVP design process. You take priority need areas, build features in a short amount of time and at minimal expense, and then get it into the hands of the customer for feedback. IDEO prototyping process is iterative as the MVP approach. You build in small incremental steps, checking for progress towards meeting the functional and emotional needs of the customer. At each design interval, the fidelity of the solution increases, providing the design team and the customer with a clear view of the solution experience.

In the shopping cart design, the teams develop four mockups, each cart illustrating how to solve one of the four need areas. Then, each team shares its design to solicit input from the group. After the review, the leadership team meets with the four teams and suggests additional modifications before integrating the four designs into the final design. This next iteration aims to look at each mockup and see what it will take to ready it for integration. As Dave Kelley says, “You take a piece of each of these ideas, back it off a little bit, and then put in the [final] design.”

“Fail often to succeed.” By the time we get to this stage, the teams have deviated from the initially defined need areas. I hypothesize that there was some loss of focus, possibly due to the time pressure. The goal of this project was to demonstrate the IDEO design process. I think they have achieved this objective. The challenge results show both successful design outcomes and some ideas that are not quite feasible in the current 1999 environment. For example, having a scanning device on the cart has only recently come to fruition, thanks to Amazon (and even this innovation is in limited use).

The final portion of the video shows the cart being demonstrated in the store environment by the team. As an audience, we watch a short walk-through of the cart’s functionality and a sound bite with comments solicited from store employees. The video ends as the feedback loop is closed for this iteration.

Conclusion

This 1999 Ideo video showed the world what design thinking is and, I believe, created the spark resulting in the design thinking movement and a significant step forward in the product innovation process. There are many vital lessons from the highlighted design process throughout the video. After reviewing much of the research on brainstorming up until recent times, it is clear that IDEO was way ahead in their understanding and practice of these techniques. Many of the practices shown in the video are now considered best practices in implementing brainstorming and other aspects of the design process.

The third part of this series will look at IDEO’s culture and its impact on an organization’s capacity for sustained innovation.

Part Three: On Culture

In this final post on the IDEO Shopping Cart Video, I will explore the firm’s depiction of its corporate culture. Creating a culture that breeds innovation is a significant theme of the video, and there are many prescriptions regarding specific corporate policies and practices. Finally, I will explore which of these practices hold up in today’s corporate environment and how they should impact the thinking of early venture founders.

As mentioned earlier in this series, I have shown this video since its first appearance on ABC Nightline in 1999. At that time, I investigated the cognitive and behavioral elements of sustained corporate innovation for a few years, including teaching several courses on the topic. Having access to a relevant case on video to share with students was a rare opportunity. I felt that this video provided several lessons on corporate culture and innovation to explore in the classroom from my first viewing. Even today, I still feel the same way. So let’s see if I am right to feel this way in today’s environment.

Organizational Structure and Innovation

At the beginning of the video, the commentator highlights that the story you are about to witness is not what you may think of as a traditional corporate environment. “It used to be that you deferred to the boss….the boss is always going to have the best ideas…not likely.” And so the video begins flipping back in forth from an old black and white newsreel of a large typing pool and clips of teams working at IDEO. Everything is orderly and hierarchical in the old newsreel, while the IDEO clips seem more chaotic.

The video starts with a core message that organizations structured hierarchically will have a challenging time being innovative. However, as you will see, even within the IDEO story, there will be evidence that sometimes hierarchy is just what is needed.

When I started investigating how to create an organizational culture that could generate sustainable rates of innovative products and services, there was a great deal of discussion about how organizational structure enables or hinders innovation. However, as in any dynamic situation, many factors determine the cause and effect of any one action, let alone a series of interrelated activities. For this reason, I have always viewed organizational behavior and performance through a lens of a system.

My earlier research focused on large, technology-driven corporations, mainly in the US. These corporations were good subjects to study since they all had large, complex structures, and their ultimate success was reliant on continuous innovation. However, trying to tease out what structural policies and practices could drive new product innovations is no easy task.

Autonomy | Empowerment

Throughout my early studies, I discovered across years of innovation research that employees and teams need to have the optimal degree of autonomy. For example, in my work at Stevens Institute of Technology, I measured autonomy by the degree to which employees reported the freedom to decide how to carry out projects and make allocation and spending decisions. These large companies certainly had hierarchical structures but had specific practices to create space for teams to work with autonomy.

One critical structural practice is the institution of a formal stage-gate process (Cooper, 1993). The formal stage-gate process is a systematic process for moving a new product project from concept to commercialization, integrating the activities of multifunctional teams. Commonly called new product roadmaps, many highly innovative organizations use some version of a stage-gate process. In the IDEO video, you observe as this multi-disciplinary team works through a formal process, from early exploration to prototyping to testing. Each phase has explicit criteria to achieve before the team moves to the next step, thus the “Gate” before the next activity stage. As discussed in the last post, the project did have explicit criteria, including cost, development time constraints, and customer need areas defined during the exploration phase. One explicitly observes the gates when the work stops and what “can only be called a group of self-appointed adults” would come together to discuss status progress. This leadership team review is an essential component of the stage-gate process when leadership and the core product team gather to review progress against specified criteria. This review determines whether the team moves forward or reverts to the previous phase (and sometimes calls an end to the project itself). One of the significant benefits of this structured product development process is that it allows the team to work autonomously in between the gates. Having clear project criteria enables management to step back and let the teamwork autonomously within the established boundaries.

In Tom Kelley’s book, he describes the “studio” type structure that they adopted some of the characteristics found in film development. By quickly assembling a project team, they could create a project environment where the members were passionate and ready to take risks necessary to think divergently and then converge on an executable solution. The overall structure allowed the employees to pick their team leader based on the leader’s description of the type of work they favored. Within each of these self-selected groups, sub-teams form for specific projects. Project teams work with studio members or across studios. These studio groups last for a couple of years, and then there are opportunities for employees to move around. This system allows for a great deal of cross-fertilization of ideas and talent.

More innovative corporations would look for ways to structure autonomous organizational groups to address more disruptive innovations in my research. One such practice is the establishment of separate organizations designed to explore new business ventures allowing for a sub-culture focused on higher levels of risk. For example, AMP, a multi-billion dollar company, recognized that while they were proficient at incremental innovations, as demonstrated by its high rate of patents, breakthrough innovations take a particular focus. Setting up a separate division as an incubator for significant new business ventures provided the structure and culture to grow risky new ventures. The company puts its money where its mouth is by allocating sufficient resources to create new business outside the core product lines.

These practices provide a suitable climate for employees to feel empowered, leading to innovative behaviors and outcomes. Research has added to our understanding of Empowerment and how to best define it. Spreitzer (1995) defines Empowerment as a multi-dimensional set of cognitions, including meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact. Empowered employees perceive their work as personally meaningful, believe they can successfully perform tasks, have the freedom to choose how to conduct these tasks, and that their efforts make a difference to the organization’s goals. Breaking Empowerment down helps select a suite of organizational practices that reinforce these perceptions in their employees, thus establishing a foundation for innovation.

Advocating New Ideas

IDEO clarifies that building up the required skills for teams to optimize the deep dive process and brainstorming is critical to its success. As Tom Kelly states, they continually experiment and find new ways to make the most of their innovation processes. Many of the companies I have investigated make innovation process training a priority. For example, 3M established training programs targeted first-line supervisors to teach them “how not to kill a good idea.” The training program creates an awareness of how even simple facial expressions and body language could send a negative message about the idea’s merit.

At 3M, every idea counts. One senior 3M manager described a brainstorming technique used to keep the idea pipeline full: “We typically use about six people from R&D, Marketing, and the business. We invite any number of end-users. They’re told when and where to meet, and when they show up, the facilitator stands in front and says, ‘Okay, the subject is this, go.’ And then they start throwing out ideas. We collect and store all those [ideas] and give them all kinds of keywords so we can sort them out and massage them later.” No matter how seemingly inane, each idea generated is recorded in a massive corporate-wide idea database. Employees from anywhere in the organization can draw inspiration from exploring this centralized database of new ideas ranging from new product concepts to radical applications of existing products.

One common practice that 3M has established is a mechanism that gets the customer or end-user to participate in the very early stages of the innovation cycle. Approximately 40 to 50 times a year, ideation groups form to brainstorm and document new product ideas. While many companies may use focus groups as part of their market research, 3M takes it further. These ideation groups comprise several customers, two members from the R&D laboratory, one marketing representative, one member from the business development group, and an outside facilitator. Their approach is genuinely multifunctional from the early part of the innovation process. (Another interesting aspect of this story is the very tight linkage between the R&D functions and marketing. This relationship is a common practice for world-class innovating companies. The integration of these two functions is much less so in poorer-performing firms.

Innovative organizations instill a sense of “advocacy” to support idea generation and exploitation. When employees begin to champion new ideas, innovation happens. In such a culture, there are no “bad” or “crazy” ideas — only unworkable ones that have been tried and failed at a specific period. Thus, lessons learned and shared experiences emanate from the company’s history are relevant. Moreover, such a culture implies that reasonable risks and failure are accepted and tolerated. In contrast, when advocates are squelched and discouraged by management practices or ignored, the drive for innovation is diminished.

Collaborative Team Structures

Another structural practice prevalent in the IDEO video is the creation of teams that are both multifunctional and cross-disciplinary. Again, this is not the only type of diversity associated with high levels of innovation, as discussed in an earlier post (ADD LINK), but still an essential part of breeding high rates of innovation. In IDEO, teams select project members primarily for their diverse experience and functional skills. This team selection policy is prevalent across many innovation studies.

In my studies, while reviewing memos and meeting minutes of various innovation teams, one notes the frequency of technical, commercial, and manufacturing people interacting early in the innovation process. For example, during the early stages, Corning scientists would informally discuss with marketing representatives the technological progress in learning how glass reacts to various methods. Both marketing and technical scientists would then, in turn, go to multiple potential end-users and discuss possible uses. This communication cycle would continue throughout the various stages of innovation – from the very early stages of exploratory research through production. In this case, scientists from R&D worked with the commercial side intensely throughout the innovation cycle. There is never a formal hand-off to development or production at Corning.

Inherent in this example is the high degree of collaboration between the technical and commercial communities. This relationship is a genuine partnership in Corning, and management institutes several practices to ensure this collaboration continues. For example, the company holds annual technology fairs for business unit associates and the scientific community to interact – for the commercial side to see what advances in glass technology exist – for technical associates to hear what the marketplace is requesting. The formal job-rotation program further encourages these interactions between scientists and business associates. In addition, new scientists spend up to a year in a business unit to learn the market and business realities and, more importantly, forge informal contacts in the business units, which will continue throughout their careers. So while scientists continue to explore and learn more about what is feasible technologically, they concurrently are made aware of potential market needs. This type of collaboration is a joint cultural event at Corning.

For most employees to become genuinely collaborative, specific social skills are required. Training and development opportunities in communication, conflict resolution, listening skills, and performance feedback provisions are especially desirable. In addition, teamwork and job rotations are encouraged to maximize the opportunities for collaborative behavior. Both Ford Motor Co. and Corning, for example, have a very formal program for getting researchers to collaborate with their business units. New hires in research are sent out for up to two years of rotation to meet colleagues in the line organizations. This formal program helps employees create informal networks of colleagues to support innovation efforts throughout one’s careers.

Goal-Directed Leadership

One of the major themes of the IDEO video is the idea that a hierarchical structure stifles innovation. Many earlier innovation studies suggested that concerns around status differentiation and “deferring” to the boss lead to suboptimal solutions. The issue is not the structure as much as the culture. Most recent studies conclude that some hierarchy is required to implement innovative products. In the aforementioned stage-gate process, it is vital that problems to be solved be bounded by organizational strategies and goals. Organizations set parameters for strategic alignment, customer needs, time to market, and resource allocation.

The shopping cart design project had specific parameters set by management. These constraints included the 5-day design window, suggested solutions must nest with each other, and the new design cost the same as existing carts. Having clear goals and parameters enables an innovative culture by harmoniously providing a structure where autonomy and authority coexist.

Another way IDEO balances hierarchy and autonomy is through several published guidelines on how to behave during a typical design process. As noted in the last post, they had several guiding principles, delivered almost akin to sacred mantras. “Fail often to succeed.” “Defer judgment” “Build on the ideas of others .”These “rules” become cultural artifacts that help communicate desired behavior across the organization and over time.

In the end, everyone must have access to participate in an organization’s innovation activities. The only way to achieve this is to start with a clear definition of what the organization means by innovation. Unfortunately, the word innovation is so ubiquitous and broad that employees do not know what you mean. As a result, it is not uncommon to uncover a fundamental disconnect among the various employees. Often, senior management will discuss what they expect in terms of innovation, but expectations remain unclear to the rest of the firm.

Like IDEO’s innovation “mantras,” what innovation means must be clear and accessible to all employees. An organization must define what types of products and for what markets are innovations desirable. For example, will good ideas that fall outside of the company’s current market competence be acceptable? Management needs to be explicit about what will happen to such ideas outside of the purview of the corporate strategic interests. Will the employee be encouraged to try the new concept on their own? Will these ideas be cataloged for future investment? Etc.

An excellent example of a precise definition from my earlier studies is Intel’s use of Moore’s Law as its guiding principle and strategy. It is clear to all Intel employees what is the desired innovation. Namely, anything that will satisfy Moore’s Law – increasing the density of active elements on a semiconductor chip – is acceptable innovation. Other concepts outside of this domain are recognized and dealt with in particular ways.

Final Thoughts

I have attempted to reflect on the relevancy of IDEO’s Shopping Cart Design Video in 2022. Each section – on diversity, the deep dive, and innovative culture – looked at how these topics from a 1999 perspective and how it serves us in today’s organizational context. Unfortunately, IDEO’s depiction of diversity has not held up well. The main reason for this disconnect is that we consider diversity issues broader and deeper than member disciplinary and functional differences. Today, we view diversity from all perspectives, demographic, inherent traits, cognitive, emotional, and physical differences. We also embrace the idea that diverse representation is just a starting point. Organizations must create policies, practices, and systems that support equity and inclusivity. In addition, organizations must put policies and procedures to ensure that diverse people are treated fairly. The ultimate objective is to create an inclusive culture that celebrates all employees’ and stakeholders’ inherent worth and dignity.

IDEO’s design process holds up quite well in 2022. However, it is factual that most organizations are still trying to catch up to their highly effective processes. IDEO was ahead of its time and, from this head start, has continued to evolve and improve its design knowledge and practice. The video still works well as a teaching tool for founders looking to integrate design thinking into their venture teams.

Finally, we have certainly come a long way in understanding what it takes to create an innovative culture. This statement is especially true in terms of academic study and theory. However, there is still much to learn about how to direct and engender the culture required to meet business and social objectives. There are books written about IDEO’s culture, and there are many lessons a founder can apply to their evolving enterprise. In the end, culture starts with the founders. Your values and resulting behaviors drive the early development of the internal culture and how the outside world perceives the venture.

© 2022 Venture for All® LLC. All rights reserved.